Now that I’m not sure of. Sounds from @jmday’s answer that it’s undecided whether the author contacts all of those 25 nodes or whether they just toss it to one of the nodes (the one whose address is closest to the transaction’s address from the author’s perspective). My hunch is that it’ll make the most sense for the validators in the entry’s hash neighbourhood to take responsibility for saturating the DHT up to the expected 25 copies.

Two or more entries, depending on the design. Your guess about multiple neighbourhoods is very right. In the simplest case (non-transactional stuff like blog posts), you have one entry with one author header/signature on it. That means you have to get two separate neighbourhoods to validate your stuff — one for the entry, one for the header. In addition, whenever a header is published, the validator holding the previous header expects to be told about it so they can keep track of whether the chain has forked. That means you have to talk to three different neighbourhoods to get your entry published!

It gets more complicated for transactions. In the simplest design, you have one entry with two author headers/signatures. That means one neighbourhood for the entry + one neighbourhood for each of the two headers + one neighbourhood for each of the two previous headers = 5 neighbourhoods, each with 25 validators! If you and your counterparty are trying to commit fraud, 125 people is a lot of people to try to deceive.

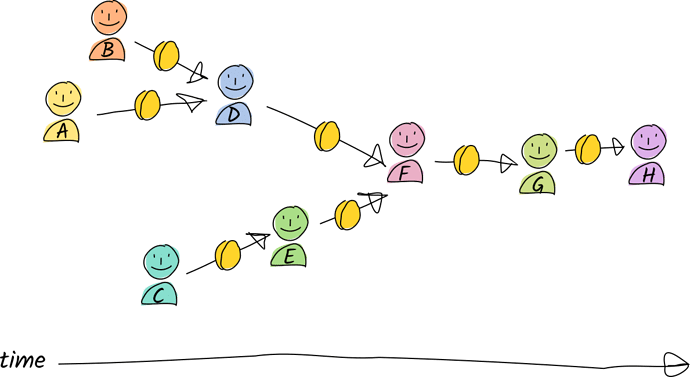

HoloFuel goes one step further still. Rather than one entry with two signed headers, each transaction consists of four entries, each with its author’s signed header. In addition, the signature is duplicated inside the content of the entry itself. Each step in the flow consists of a signed ‘envelope’ around the details of the step, which may consist of the previous step’s signed envelope. Here’s how it looks:

- Initiator proposes a transaction — either a promise of payment or an invoice. 1 signed envelope + 1 header.

- Receiver audits the transaction and posts an acceptance. 1 signed envelope + 1 header.

- Initiator confirms that they’ve seen the acceptance. 1 signed envelope + 1 header.

- Receiver confirms as well. 1 signed envelope + 1 header.

This makes (4 entry neighbourhoods + 4 header neighbourhoods + 4 neighbourhoods for previous headers) * 20 resilience factor (made-up number; might be less or more) = 240 neighbourhoods who have witnessed at least some part of the transaction! In addition, each step contains the signature of the author and all previous signatures on all previous steps, so it’s a pretty robust audit trail.

This is something I’m not entirely clear on. I do know that a validator can attach a warrant to their copy of an entry and share that warrant with its neighbours, but it would be almost as expensive to search for those warrants as to manually audit each counterparty’s transaction history. I wouldn’t expect warrant-checking to be mandatory — that should be an app creator’s decision — but I would like to see settings to make it easy for an app creator or user to have their Holochain do that at the subconscious level.

And it wouldn’t have to be expensive, because it wouldn’t have to be manual. As long as I can trust the validators who approved the last entry + header, I can trust the entire transaction history. Why? Because I trust those validators to have done their homework, which means that they made sure they trusted the previous validators, who made sure they trusted the previous validators, etc.

An alternative quick path would be to allow a warrant to be attached to an agent entry. It’d be very difficult for a malicious actor to control the neighbourhood they’re in, so this would be pretty reliable and would require only one lookup.

‘finality’ is always a probabilistic thing in eventually consistent systems, so it depends on level of trust vs risk involved in the transaction. Finality would probably mean “a quorum of validation signatures has been collected for the entry”, where ‘quorum’ = the resilience factor. Validation can be parallelised, but you’d still need to consider the time involved in making a network connection to each validator and waiting for their response.

‘finality’ is always a probabilistic thing in eventually consistent systems, so it depends on level of trust vs risk involved in the transaction. Finality would probably mean “a quorum of validation signatures has been collected for the entry”, where ‘quorum’ = the resilience factor. Validation can be parallelised, but you’d still need to consider the time involved in making a network connection to each validator and waiting for their response.

we have a local consensus about it.

we have a local consensus about it.